Our invisibility is costing us lives

A conversation with Out Boulder County's Executive Director, Mardi Moore, on LGBTQ+ discrimination in health and care services

Thank you very much for agreeing to this. You are the executive director of Out Boulder County, an association that advocates for the rights of LGBTQ plus people in Boulder County, Colorado. Is that correct?

That is correct. My name is Mardi and my pronouns are she, her and hers.

So what does Out Boulder County do in your community? What are its activities and purpose?

Well, you know, I cannot talk about today and where we are going without talking about where we've been and how we started. In the state of Colorado in 1992, there was something called Amendment 2 that our friends and neighbours and family voted on. And it was about ensuring that LGBT people would not have any rights, any protections around public accommodations, etc. And that case went to the United States Supreme Court in a case called Romer v. Evans. If you look at the history of all LGBT groups, those that are surviving, most of them were formed between 1992 and 1994. Colorado was known as the hate state, and people were cancelling their convention trips here and but Jean Debowski, who lives in Boulder took that case pro bono all the way to the Supreme Court, and we won, and that law was never enacted. But out of that Out Boulder sprang from a group of activists in Boulder County that started the first Pride Parade in the city of Boulder. And in my office today still hangs the baton that somebody carried in that parade. So, we hang on to our past, as we look towards the future. One of our staff members goes to corporations, they've trained all the district attorneys throughout the state of Colorado on LGBTQ issues. Most recently, they're working with the Boulder Shelter. There are a lot of transgender folks who are homeless in our community. And so, we are working to change systems that aren't set up to deal with our identities. We do a variety of training, and a variety of education, even in the schools through a speaker's bureau, which is our Boulder County's longest-running program called Speaking Out, where a trained group of people go in and tell their stories of coming out. And they speak mostly to allies because, frankly, the world is made up of more straight people and cisgender people than it is the rest of us. It's an amazing program that reaches thousands of kids each year. We also provide services and programs. One of the things that we knew prior to the pandemic was that LGBTQ people suffered from higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicidality, and we knew that because of our own studies, groups like the Williams Institute or Movement Advancement Project, because of course, the government's not going to tell you any of that because they don't keep track of LGBTQ identities in national data. There are a few exceptions, but they're pretty sparse in what they collect. In March of one of these years during the pandemic, two trans people who were connected to the periphery of the organization died by suicide. And we know suicide is a lagging indicator of poor mental health. And at that moment, I called one of our local county commissioners and they said you all have to give us some money now because people are dying. And we need to set up a program because the systems that are put together are not serving us. And we know that from individuals going to local mental health services, and saying, «Wow, that was not a good match». For example, a gay Mexican man, now with American citizenship, was working towards citizenship during the time of Donald Trump. He was stressing out as you can well imagine. He goes to a therapist, and, he tells the story of fear and anxiety. And the therapist said, «there's not that much to worry about». Now, that kind of response, not understanding the intersections of gay identity, immigrant identity, along mental health, keeps people sick and leads to really poor outcomes.

And so I've been the executive director for just over eight years. And one of the things that have been terrible since I've been executive director was one, the massacre in Orlando. And after that tragedy, that day, we held a vigil when we brought together faith leaders and community members and had a vigil.

And that’s when we started working with law enforcement also because we know for all kinds of reasons that the LGBTQ community has some suspicions that are well-founded. During the presidency of Donald Trump hate crimes and hate incidents in Boulder County spiked, even before the inauguration. We started getting reports and the whole time I had been here prior to that I'd had a couple of people reach out to us around hate incidents or hate crimes, looking for assistance with the police. We had an incident not long ago at a municipality, within our county, where a genderqueer person who appears to many people as male reported an assault. And the police officers, his response was «why didn't you just push him away»? That's not right. So we know the level of work that we have to do and the level of training for the LGBTQ community to have any safety in reporting incidents, such as sexual assault or hate crimes. I try to run as a buffer and get things reported and make sure crimes are investigated well.

And then there was Covid

So here comes COVID. Now, we did some quick surveys ahead of time, because we know that we're economically disadvantaged that more of us live in poverty than don't. And that's what the numbers proved. In 2013, in Boulder County, there was a historic flood. Local and national news was here with helicopters. It was a terrible, terrible thing. And one of the things that two women noticed, Carmen Ramirez and Marta Lamine, who is currently a county commissioner, did a study called Resiliency for All and in that it was found that the people who didn't recover well from the flood or suffered the most were communities of colour. And there are I could be wrong, but I don't think there was a mention of LGBTQ communities in that. But because of that, and because of that study, our government systems started putting in place what they call cultural brokers.

So when the pandemic struck Boulder County pulled together a group of people, LGBT people, brown people, black people, disabled people. And every month, they talked about a different issue, whether that be child care, mental health, down through the list, financial impacts, and then the word of the vaccines came. And in that conversation, Caitlin Gray, who is a psychological researcher, was at the table a member of our community, an out lesbian, and she said to the Director of Health Equity in Boulder County, would it be helpful if we had information about the LGBTQ community and hesitancy to vaccines? And the response was, that would be a gift. Did they do any tests with HIV positive men? Who was on PrEP? Or did you? Did you pull transgender people in who were on larger amounts of hormones? Is there any? Is there anything going on there? What about pregnancy? What about like, all these things, and there wasn't any information coming out from our federal government about any of those populations? Why? Because we weren't included in any of the stuff they did in their clinical trials. We started addressing all the barriers that our local public health system has in place, not because they think about it, but because it is and they don't think about it. So language, like most of all the materials were in English, nobody had even thought about showing up to a vaccine clinic with someone who speaks Spanish. We worked with that and built a fantastic relationship with a local Latino group called El Centro Amistad. Then we added Craig from the Center for people with disabilities. In fact, I spoke at a CDC Foundation panel last week, and their great minds are now thinking about modernizing the data. And like reimagining public health, and I think it took the pandemic to do that.

Two weeks ago, somebody from the county reached out to us and said, What's the food insecurity like in the LGBT community? I actually should be asking them, right. And so, you know, here we are this little team of 12 people, like pulling all the data together without funding for systems so then we can figure out how to break down the barriers to get our people to food, this, this is a broken system.

About collection of data. Recently, you published what may be the nation's first LGBTQ+ and BIPOC lead survey on vaccination intake. What were the results of that survey?

You're referring to our Youth Survey. As a whole, trans kids, youth, gay and lesbian kids, bisexual kids, and kids of colour, are less hesitant and more vaccinated than adults. What we found in our survey, is that white, poor cisgender youth are the ones with the most hesitancy and least likely to be vaccinated. So what I do in my mind, and again, it's apples and oranges, but I feel like our education work around the vaccines has been successful. Because we've seen this increase in vaccinations. We help however, we held the vaccine clinic yesterday, the big bus from the state came in, and I think we vaccinated 48 people yesterday. And we're going to continue I think we have three more clinics through spring, we will continue to vaccinate people. Usually when you think about it, like «oh, there's a connection between race and hesitancy», the racist mind jumps to people of colour. When we say race is a barrier to vaccinations, it's white people. And that is because in my opinion, the last administration under Donald Trump politicized public health, and they continue to do it. We are at a level with people that are never going to get vaccinated. Someone I know died this week of COVID Somebody from my hometown, and I know what their political leanings were. They weren't vaccinated and left behind kids. A good guy got caught in the trap of this misinformation and this political politicization of a vaccine that's effective and saved your life. So it's heartbreaking. We're where we are in the United States and I don't think we're unique.

I'm so sorry. We also have stories here about this ideological mistrust towards vaccination spurred by political propaganda. Talking about mistrust. Historically is there has been a bad relationship between the community and the medical institutions in the United States. Something, of course, related to the history of the community. In America, especially, when we talk about pandemics the mind goes back to HIV. So, do you see the same pattern? Do you see some of that mistrust in the data?

There is certainly mistrust and, you know, you're right, it started with AIDS. It was 1982 When I came out, and that was the beginning. They didn't even call it aids then, but Grid (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, n.d.r.). There is still that mistrust. When I go to the doctor, for a Pap test or something, I still have these old tapes that run in my head «they're going to find out, I'm a lesbian, they're going to be weird about it». that breeds more mistrust. And that's me and I have money to go to the doctor, I have a health care plan. But when you live in a world that doesn't accept you, it, as a rule, invades every part of you. there's nothing inherently wrong with us. But after you get misgendered a million times or somebody yells at you, or send you a fax, they still send faxes, people telling you «you're gonna burn in hell». Like, I know, that's not true. But after a lifetime of churches telling you, of government systems not seeing you, of course, that is going to influence the medical industry. And there are so there have been some changes made, certainly not enough.

You speak all about collecting data as a key, to the visibility of the community in the US, but what's the attitude of members of the community towards government taking, collecting data like sexual orientation and gender identity?

Oh, there'll be pushback, I assure you, you've nailed on that there. And that's why I say optional. Everything about this is optional. I think there's probably, even more, fear coming out of the Trump administration when I wouldn't want him to have information on me. And I think there's something similar that when marijuana became legalized, you had to sign up and people didn't want to put their name on that list, like, for good reasons, right. I think it'll become normalized after a while, but my people are sometimes mad at me for even suggesting this. I asked one of the vice presidents of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation when GRID started «can you tell me why the Federal Government didn't begin collecting sexual orientation, then?». And you know, we still didn't exist, although there are health reasons to have this information. You can't address issues without data. It'll lead to the strengthening of LGBT small groups like Out Boulder throughout the country if they could actually have that data. Because not everybody has a research team. Like we're slowly building our own little research team because we have two. There's a statewide organization, a great organization called One Colorado, but they haven't done a statewide health equity assessment of our community, I think since 2018. And so that's one piece of the work, but I think that data will affect systems in such a way that it will strengthen programs that serve our community.

I think also about the fear many people feel giving information about their identity to the government. Now they are trying to help them but, in the future, they might try to hurt them.

That’s exactly right. And so there has to be a lot of data security built into the programs. You know, for the census, for example, they say this information will never be shared. Yes, it will. There's at some point, you know, it's decades later, but that information becomes public. And so, we want to be clear, about how this data is going to be handled. We have the Colorado Division of civil rights. If a doctor acts on that information and all of a sudden, you're discriminated against, there's a government system that would come in and deal with that situation. You have to have safeguards throughout, I'm one of those who like to check information off a form because It's important, but I do it and think «oh, there might not be any ramifications?» No, I'm not an idiot. Like I've been around the block long enough to know that, you know, systems are what systems are. But if we aren't seen in the data, the system is never going to change.

Talking about Colorado. When we think about it politically, it's like an island, famous for being one of the most LGBT friendly states in the Mountain West. Is it because it's Democratic-leaning? Or there are more reasons?

You've done your homework. I was born in Colorado, I have lived here the majority of my life, but I've been in New York City and Houston and Seattle for 20 years. So I've lived ever other places. My family was made of coal miners and ranchers, that’s how they ended up here. And you know they’re big libertarians, they call them independent in the polls. Like «leave me alone. I want my gun. I want my dog, my little woman at home. Government stay out of my business. don't vaccinate me». But then we had Pat Schroeder, one of the first women in Congress back in the 70s. She's still alive. And then we had some people like that who showed up kind of early on and at least in my lifetime, that made Colorado think differently. Like «wow, women aren't at the table? Wow». But Pat Schroeder was. We also have a big ski industry. So it brings people from all over who probably stay and bring other you know, East Coast or West Coast ideas along with them. There's something like that in my own community. I live in Longmont, which is a city in Boulder County, that takes its name from Boulder, a college town. My parents live in Longmont. They say «don't boulderize Longmont» like «don't bring your wild ideas over here», you know, wild ideas like treat people with kindness kind of stuff. So is this cowboy mentality that clashes with a more liberal one. I'm a liberal, moderate to moderate liberal. I used to be a radical, with a little bow tie and like burn that thing down. And then I got old and realized changes were incremental.

And you know, back in 1992 when our neighbours said: «you're not going to get the rights», that galvanizes the community and has made us stronger. We've seen it happen before and it's not going to happen again. For the pride celebration in Boulder, people come from New Mexico from Wyoming, they come down from South Dakota. And so we are a bit of a hub. But it's not all great here. They say we are one of the healthiest cities but who are they really surveying? Because there are people who are walking into our office looking for help.

You talk about your upbringing in rural Colorado and your radical past. What was your experience, your political experience, and your experience with activism?

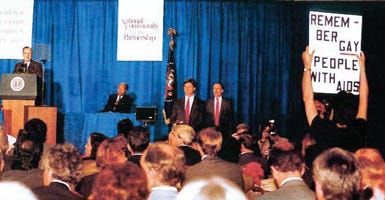

Well, I came out during AIDS. And that was scary. And then it became sad. It wiped us out, like, I have very few male friends of my age. And the ones that I have, are mostly people who came out after aids, you know, they were in marriages. It was Urvashi Vaid, standing up in a press conference with that sign.

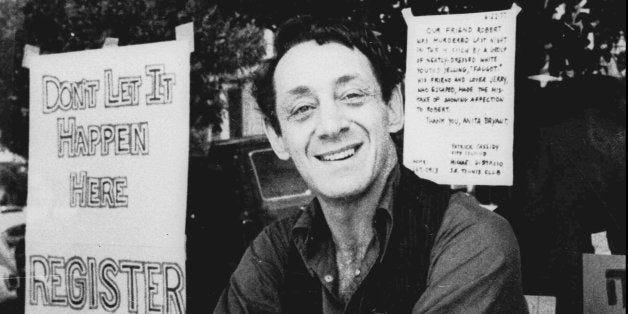

That activism changed the way the federal government worked. I think that, that that radicalized me, that's how you have to make systems change, you can't be nice and work for incremental stuff all the time. Sometimes you have to be that person that says something that nobody likes. But that moves that entire group of people forward. I have a big picture of Harvey Milk that hangs in my house. I was this little kid in a town of 3000 people. My dad was a veterinarian, it was a real rural area, you know, I was pulling calves and vaccinating cows and all that stuff as a kid. We went to a Methodist Church, so I didn't hear anything other than bad things about homosexuals.

I was always the tomboy, my brother would be inside reading, and I'd be on the motorcycles and I'd never fit, but my mom's still disappointed in me, let's be clear. You know, I'm not gonna wear that dress, I'm not gonna carry that purse. And so I never fit. And then I also had these thoughts «Oh, my God, you are a pervert», because that was a language I had. And then I went to the University of Denver. I met two lesbians, and, like a lightbulb, I'm like, «Oh, my God, I'm not a freak, There are people like me Wow». I came out when I was 18, or 19. Not to my family, God forbid, that's why I moved to Houston, «I can't tell these people and I need to go on with my life». And that took a while, you know, I thought of Harvey Milk “Come out, come out, wherever you are» when I was in New York City. The day that Edith Windsor took down the United States of America will be one of the biggest days of my life.

And I thought «one person like that can make such a tremendous difference». That's what I've always held up, one person can make a big difference. And it's not easy. And, you know, Edith was suffering from some great health issues, the stress of that. But to make it through that, and to come out the other side and Harvey Milk to be murdered over it. I was in grand marshal for the Pride Parade in Denver. And it was during the height of the Trump administration and hate was, you know, it's still on the rise, frankly. But it was it the numbers were going up, and the threats were going up. But I was scared, like, I was really scared. There's one of the famous Harvey Milk quotes that I still have in my wallet, which is, you know, «if a bullet should enter my brain, let it break down every closet door». You know, and that's kind of how I live, you just have to keep doing what you think's the right thing, ask God for help. Find people who are like-minded and keep moving.